When I was younger and significantly more ambitious than I am today, I devoured every chess book I could find. Simply put, I truly believed that all I had to do was read and absorb what the masters had written, and then—just like that—I would be as good as they were.

Book studies were supposed to be a guaranteed way to achieve success. Especially in the opening phase. Hadn’t I all too often been tricked into positions I disliked, didn’t understand, or where I was simply worse?

One book I had high hopes for was An Opening Repertoire for the Attacking Player by Raymond Keene and David Levy. I imagined it would suit me like a glove. After all, wasn’t I an “Attacking Player”? And here was a book that would tell me which openings to choose in order to always play attacking chess and always end up in positions I liked. Little did I know then that Keene is one of the most prolific writers of low-quality chess books in history. Nor did I, in my youthful naivety, consider that a complete repertoire book should probably be much thicker and more detailed than this thin little volume.

Nevertheless, I learned the masters’ variations as best I could, gaining a brilliant level of confidence in the process. 1.e4 was the magic solution, and then there were suitable attacking responses to all of Black’s attempts to dull the game.

In a tournament in Lugano in the spring of 1985, I was set to face the Dutchman Gert Pieterse, whom I knew played the Caro-Kann as black. Naturally, Keene and Levy had a guaranteed winning variation against this as well, so all it took was a quick look in the book of truth for me to feel completely prepared.

Carl Fredrik Johansson – Gert Pieterse

Lugano Open, Lugano, Switzerland, 1985

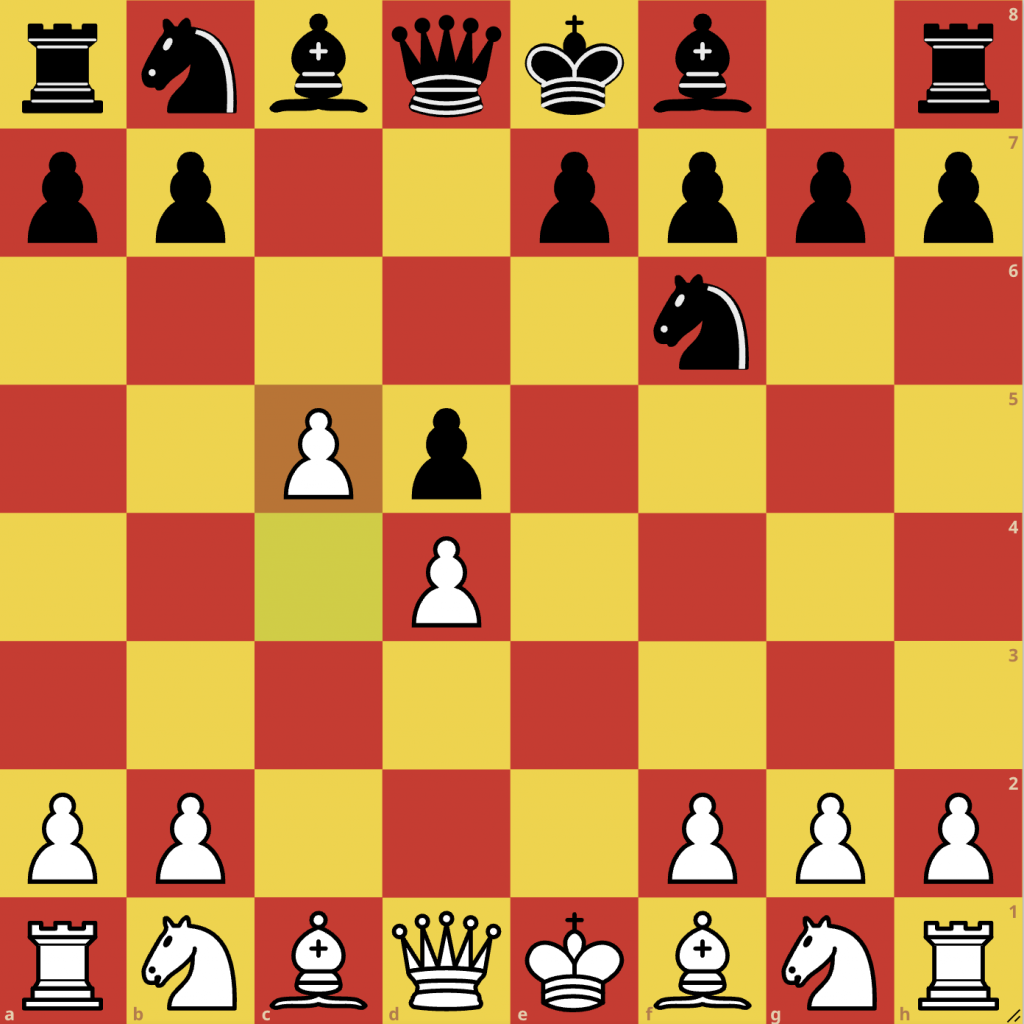

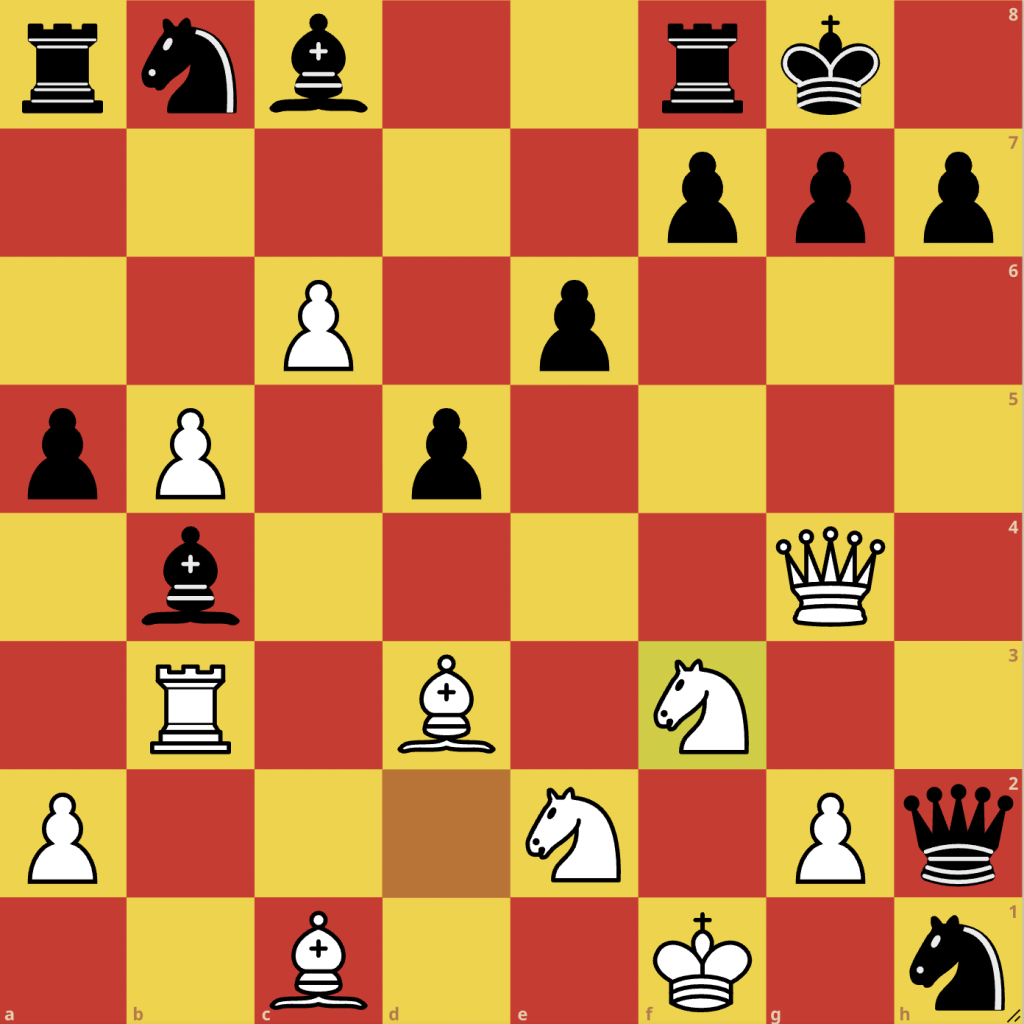

1.e4 c6 2.d4 d5 3.exd5 cxd5 4.c4 Nf6 5.c5?!

Yes, this is exactly how it should be played. It was called Gunderam’s Attack, and nowhere in the book was there even a hint of a chance for Black to equalize. White’s queenside pawns would swallow Black, who would struggle just to move his pieces. At least, that was the idea.

5…b6 6.b4 a5 7.b5 bxc5 8.dxc5

After 8… Qc7 9. Be3, the authors then write that “Black is already helpless against the combined strength of the pawns.” And 8… e5 9. c6 does not help either. So it was that simple. I’m crushing him!

8…e6!

That wasn’t in the book, but e6 or e5 shouldn’t make much of a difference. I continued as Keene had done.

9.c6 Ne4!

And suddenly I realized what a huge difference it makes whether Black’s pawn is on e6 or e5. White’s greatest weaknesses lie on the dark squares behind the ambitious pawns. If Black is to exploit this, the f6–a1 diagonal must not be blocked. That wasn’t mentioned in the book.

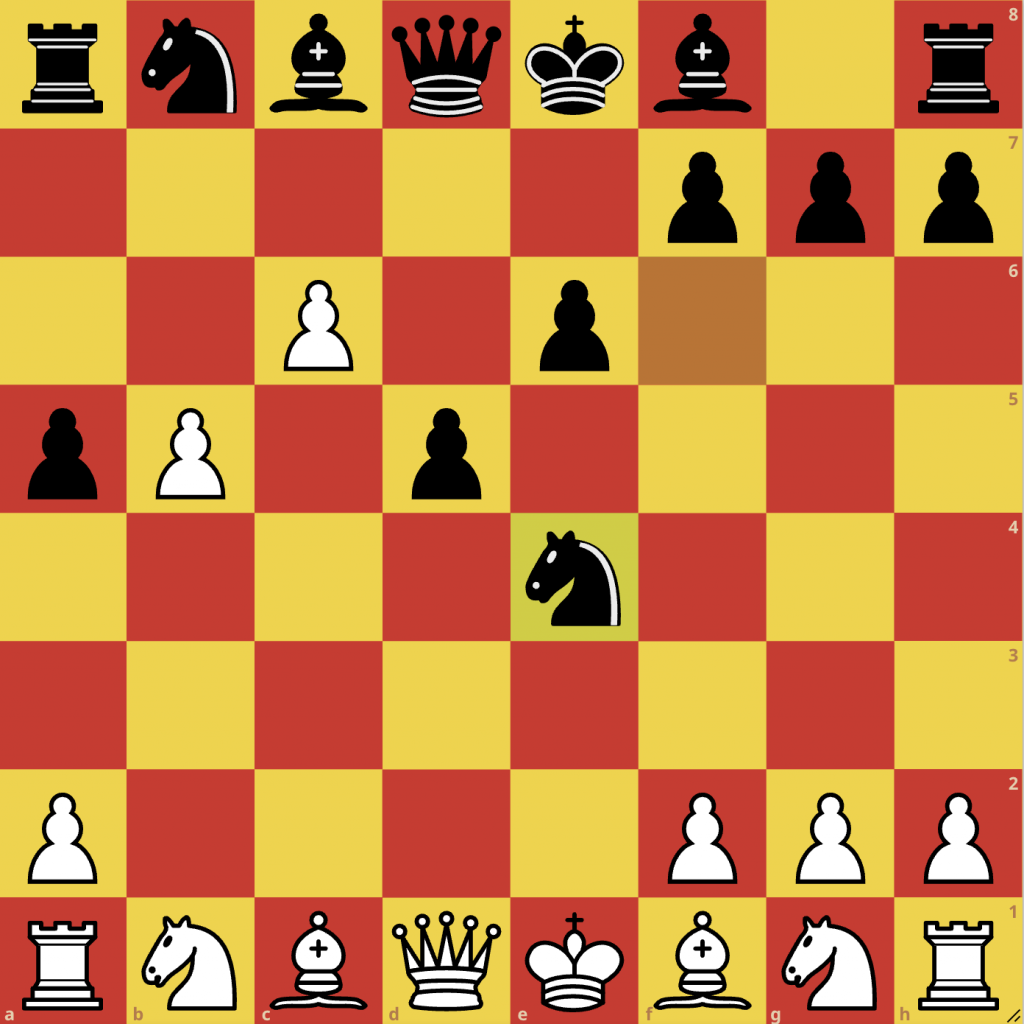

10.Qf3!?

The alternatives aren’t any better:

a) 10.Nd2 Nxf2 11.c7 Qxc7 12.Kxf2 Be5+ 13.Kf3 Bg1 14.Rxg1 Qc3+ winning.

b) 10.Bb2 Bb4+ wins immediately.

c) 10.Nf3 Bb4+ 11.Nbd2 Qb6 12.Qe2 Rc3 13.Rb1 Nc6 and everything collapses.

d) The best I have been able to find for White afterward is the following variation: 10.Be3 Bb4+ 11.Nd2 d4 12.Bf4 e5 13.Qc2 O-O!, but it seems like Black gets a much better position in all variations.

That was hardly what I had dreamed of before the game. So everything seems terrible. But those who don’t think for themselves always have only themselves to blame. Here ends the moral lesson. As Bent Larsen said – I don’t think you should burn all chess books, just the theory books.

Despite this opening debacle, the game actually lasted much longer than I deserved. For those who want to see an example of real Hawaii chess, I’m happy to share the rest of the adventure.

10…Bb4+ 11.Nd2?

The only way to avoid an immediate loss was 11. Kd1. But how fun does that look?

11…Qb6!

Threatening 12… Rc3 13. Rb1 Nc6! Already here, Black is winning. But it’s not enough to have a winning position; you also have to win.

12.Bd3

12.Rb1 fails to 12… Nc6 13.bxc6 Rxd2+ and 14… Qxb1

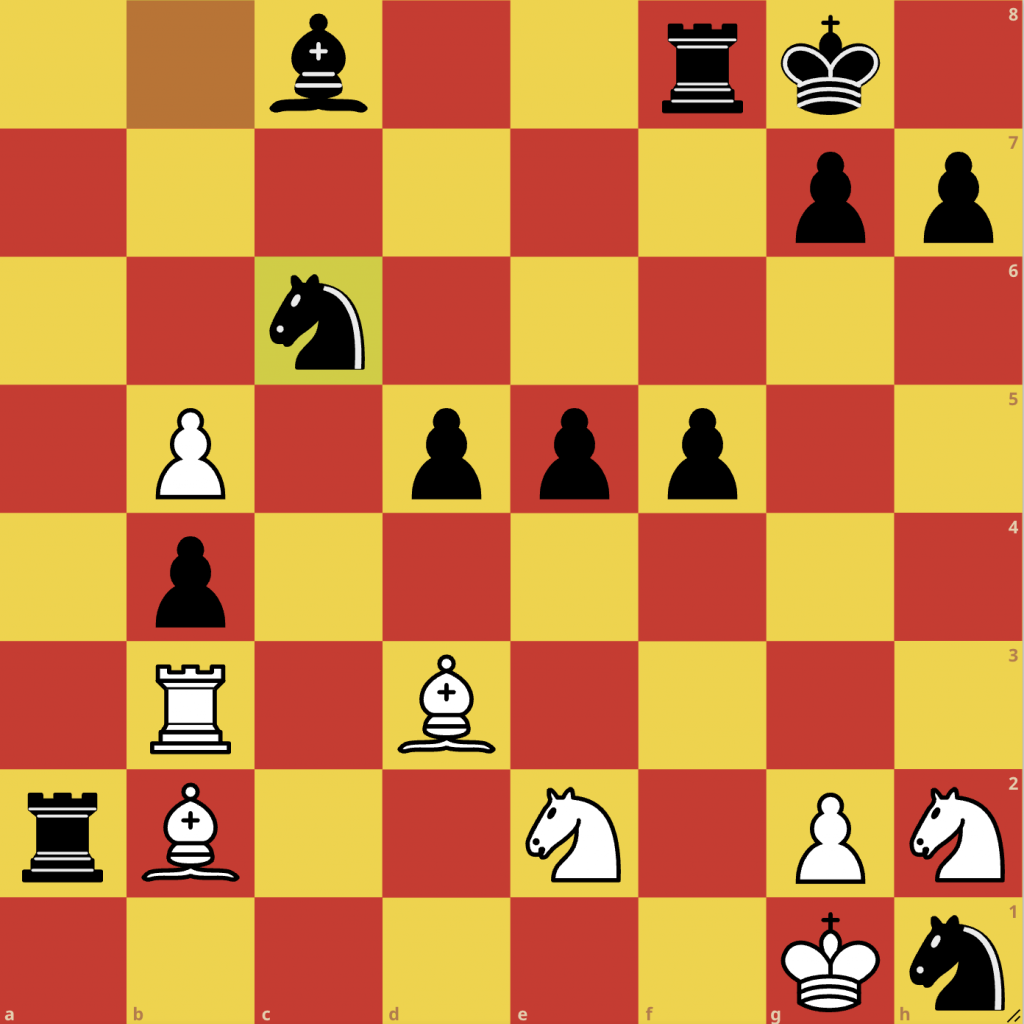

12…Qd4! 13.Rb1 Nxf2 14.Rb3!?

A crazy move. But 14.Qxf2 Qxd3 15.Rb3 Qxb5 is also completely lost. The most reasonable thing would be to resign, but instead, I went for what looked like the only possible swindle.

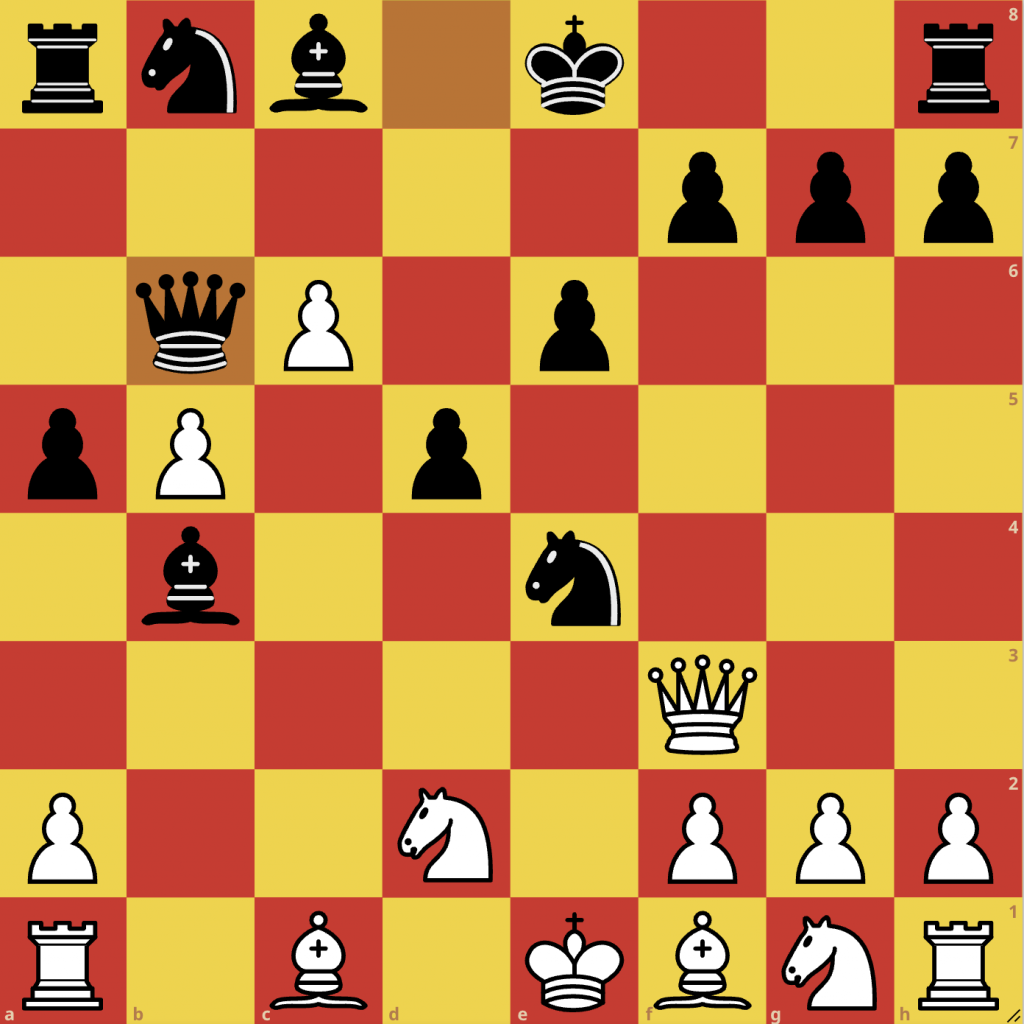

14…Nxh1 15.Ne2 Qh4+ 16.Kf1 Qxh2 17.Qg4!?

Should he avoid 17… g6, 17… Bf8, or some other move that secures his winning position, or should he let me stay in the game a little longer?

17…O-O??

Thank you, thank you. Now “resign” is no longer an option.

18.Nf3!

18…f5!

A piece sacrifice, but if 18…Qc7 then 19. Bxh7+! Kxh7 20. Qh5+ Kg8 21. Ng5 Rd8 22. b6! and I am the one winning.

19.Qxb4 axb4 20.Nxh2 e5 21.Kg1 Rxa2

It’s hard to get the pawns moving. 21… e4 22.Bxe4 Ra5 23.Rxb4 Ba6 24.bxa6 Nc6 25.Rb6 and White stands absolutely better.

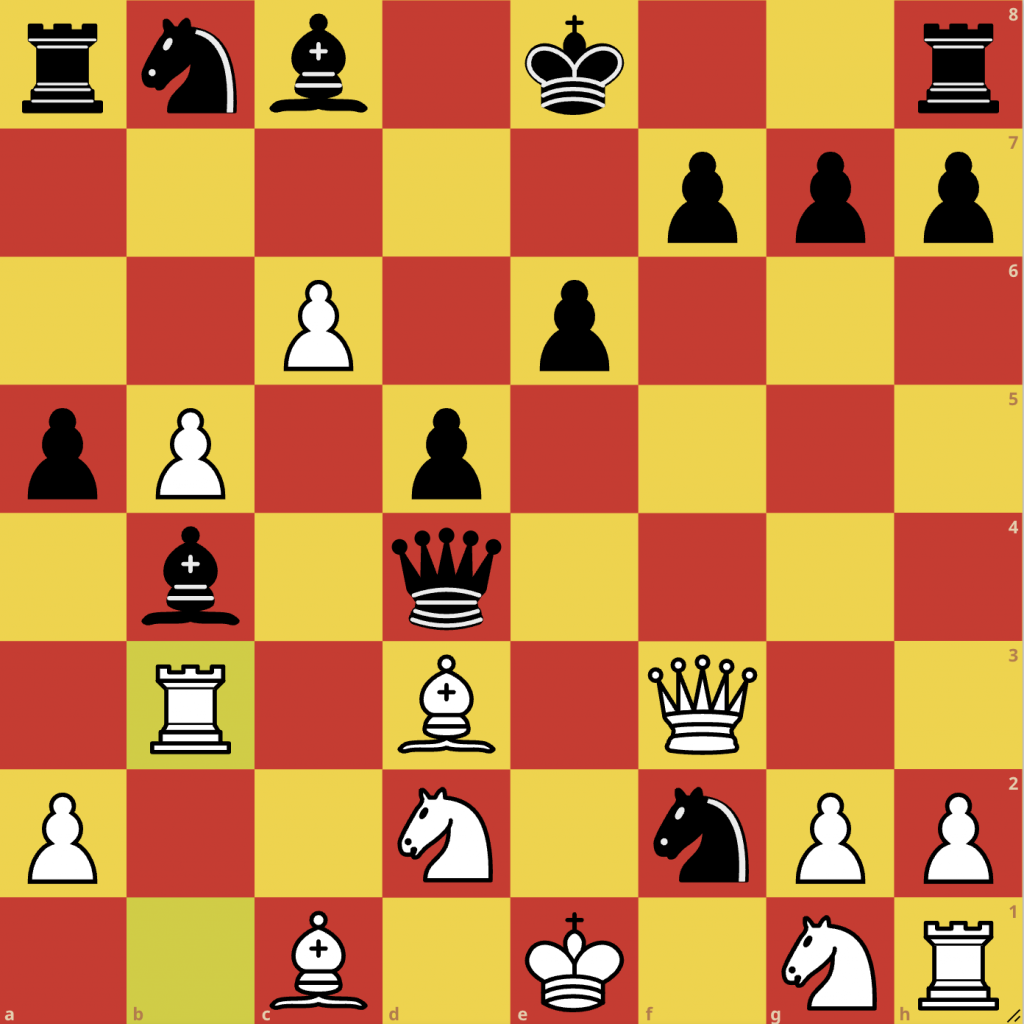

22.Bb2 Nxc6!?

This looks desperate, but Black simply cannot afford to let the knight remain trapped. Here we can actually see the only small point of the opening moves reflected in the game. The b- and c-pawns were at least somewhat useful. At the same time, it is not at all easy for Black to move the beautiful central pawns without weakening them. An example is 22… e4 23. Bxe4 Ra5 24. Rxb4 f4 25. Kxh1. Materially, it is roughly equal (believe it or not), but my passed pawns are just as dangerous as Black’s.

23.bxc6 Ba6 24.Bxa6 Rxa6 25.c7 d4 26.Nf3 Ra5 27.Kxh1 Rc8 28.Nexd4!?

Here one might consider investigating the interesting endgame with three pieces against a rook and four pawns, but it felt like there had been enough strangeness for one game. That investigation will simply have to wait until the next time the opportunity arises. Instead, I simplified with another piece sacrifice.

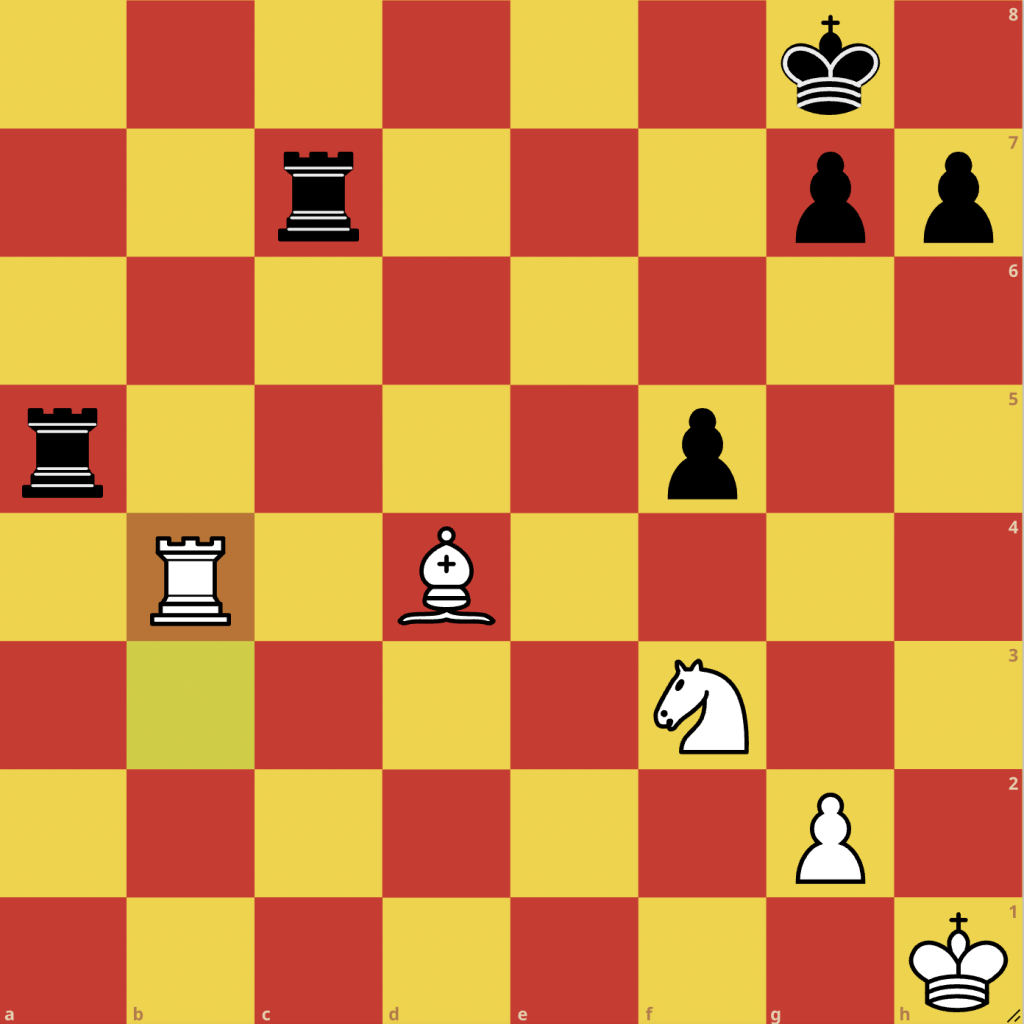

28…exd4 29.Bxd4 Rxc7 30.Rxb4

Neither I nor Mr. Pieterse really understood what had happened. It is still the same game! A lot has happened in just 30 moves. Now it should be a draw, but we fought on for a few more hours out of sheer habit.

30…h6 31.Kh2 Ra2 32.Nh4 Rf7 33.Kg3 Kh7 34.Rb8 Ra3+ 35.Kh2 Ra4 36.Rd8 Ra2 37.Kg3 Rd2 38.Nf3 Rd1 39.Rb8 Rd7 40.Bb2 Rb1 41.Kf4 Ra7 42.Nd2 Rg1 43.Kg3 Rd1 44.Nf3 Rdd7 45.Be5 Rdb7 46.Rc8 Rb6 47.Nh4 Ra3+ 48.Kh2 Ra4 49.Kg3

Someone must have been playing for a win. But who, I don’t remember.

49…Rb3+ 50.Nf3 Re4 51.Bc3 Rb6 52.Nh4 Rg4+ 53.Kh3 Rb5 54.Nxf5 Rxg2

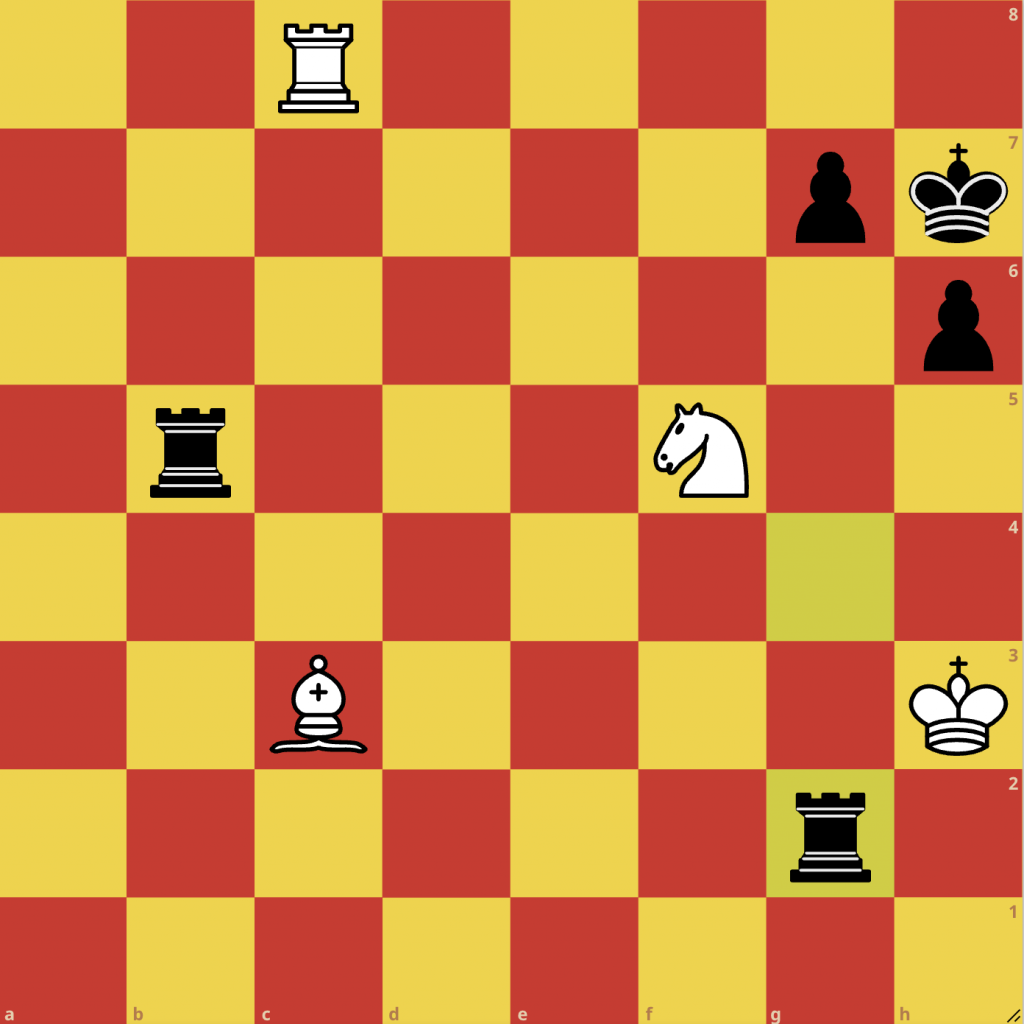

Finally, a decisive sacrifice. Now it’s a draw. I think…

55.Kxg2 Rxf5 56.Rc7 Rg5+ 57.Kf3 Rg1 58.Kf4 Rg5 59.Bd4 Kg8 60.Be5 Kh7 61.Rxg7+

In a game where a rook, three pieces, and an exchange have already been sacrificed, it is only natural that the final move is also a sacrifice. After 61…Rxg7 62. Bxg7 Kxg7, all the pieces are gone. So, finally, we could rest.

½–½

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.